Writing the Script

The brief for Professor Ray Laurence was to write a script of 140 words and to put into that 140 words as much content as possible. Sounds impossible, after all, most academic articles are around 8,000 words or more.

Here is the script for the film - 143 words in total:

Today, we think of a street as a means to get from A to B. This was not the case in Pompeii 2000 years ago. The street was a place of activity – children being taught their ABCD, water fountains from which householders carried home clean clear water, shrines to the gods of the crossroads, and the walls of shops and houses covered in painted notices for elections or shows in the amphitheatre. In fact, many of the streets were blocked to carts and others were too narrow for carts to pass in both directions. Clearly, the streets became water-logged or dirty – hence crossing stones were added to keep people’s feet out of the mud – this was an added impediment to carts. Moreover, the stone chosen to pave the streets was weak and ruts formed – navigating the city was tricky, to say the least.

Elements in the film

1) Street Shrines

The Lares Compitales were the gods of the crossroads, and they were worshipped at the crossroads of the Roman city of Pompeii. They were associated with the protection of the local community and were often represented by small shrines at the crossroads. There was an adjustment to their naming in Rome in 7 BCE, when Augustus gave magistrates of the neighbourhoods (magistri vicorum) the Lares Augusti. This year also became known as Anno I and we find in Rome subsequent years counted in this way. It is less clear whether exactly the same format was used in Pompeii, but we have good evidence for numerous street shrines across the city located close to the crossroads of the city. The image to the right shows the combination of a small altar (amongst the grass) and wall-painting to represent the 12 gods of the Roman pantheon, infront of which is a water fountain. The placement of shrines at the crossroads increased the amount of activity at the crossroads. To see more images of street shrines and their location visit www.pompeiiinpictures.com.

Street shrine behind the water fountain in the foreground. Image by Ray Laurence, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

2) Water Fountains

The aqueduct was connected to Pompeii at the time of Augustus (27 BCE - 14 CE). The water fountains are public things thus are placed in public space like this one in Via degli Augustali at a street corner - cut into the pavement to ensure it does not encroach on the flow of traffic. Note in the photo the rut from carts passing just infront of the fountain. However, as we can see from this photo, the placement of this fountain impedes a turn into the side street. If we add people into the street collecting water from the fountain, these people may have impeded the flow of traffic. If you want to see the placement of other water fountains, you can see photos of all of these by visiting www.pompeiiinpictures.com

Water fountain - notice its location and position of wheel ruts infront of it. Image by Ray Laurence, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

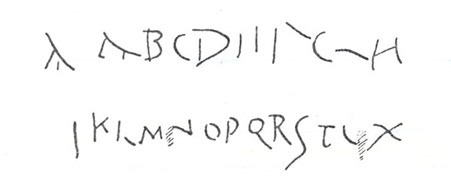

3) Learning your ABCD in the streets of Pompeii

Alphabets are found as graffiti across Pompeii, there are more than 100 examples. Some written backwards as part of the practice of being able to write letters. Notice the majority of graffiti are simply someone’s name and it would seem to have been important for the Pompeians to be able to write at least their name. The alphabet graffiti appear both in houses and on the facades of buildings, showing that children were learning to write at home and in public; whilst in the Large Palaestra (next to the amphitheatre) we find a concentration of alphabet graffiti.

Alphabets were often written on walls as graffiti to practice letter writing.

4) Bakeries

The archaeology of Pompeii has identified bakeries from the presence of both mills for grinding grain and ovens for making bread, which you can see in this photograph. The mills are made from volcanic lava that is not local and was imported to Pompeii from as far away as Umbria in central Italy. Bakeries were mostly located in accessible streets, but others can be found in streets that were narrow and only able to accommodate a single cart moving along the street - such as the street in which this bakery in the photo is located - Via degli Augustali. You can examine another bakery by visiting www.pompeiinpictures.com and examine the plan and how the mills and oven are fitted into the front of the structure, whilst in the back ther is a courtyard and space to stable the donkeys.

A bakery with donkey powered mills in the foreground, and the oven in the bakck of this shop. Image by Ray Laurence, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

5) Fulleries

The cleaning of clothes and textiles prior to manufacturing was a key urban industry, we find evidence of this in Pompeii in the form of vats for washing clothing. Famously, urine was used in the cleaning process, as was ammonia derived from pigeon droppings. The emperor Vespasian (69-79 CE) was criticized by his son for his tax on urine but responded by asking if some coins smelt - you can read about this in Suetonius Life of Vespasian section 23. These vats could also be used for dying cloth and we have evidence from graffiti and sign-writing for the presence of fullers and dyers, as well as spinners and weavers in Pompeii. You can take a look at the Fullery of Stephanus on Via dell’Abbondanza by clicking on this link.

A vat for the cleaning of cloth or clothes from the Fullery of Stephanus. Image by Ray Laurence, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0.

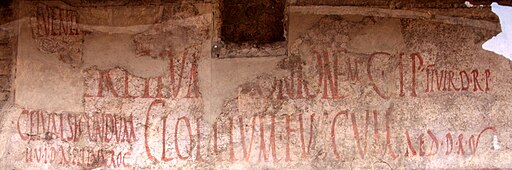

6) Information City: Notices for Elections and Shows

A feature of the streets of Pompeii were the signs written directly onto the walls of buildings. Many of these signs are painted in red letters on the upper register of the facades of buildings. You will see in the animated film a notice for the games in the amphitheatre, but the majority of the notices are advertising candidates for election to be aediles or duumvirs (literally the two men) each year. In office these men would organize the worship of the gods, the maintenance of streets, the administration of taxation and city funds; but would also give back to the community by providing games or beast fights or feasts for the people of the city. Macquarie Uni Ancient History Resources for Schools has more information on elections.

Electoral Notices in Pompeii Image by Amadalvarez, CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

7) Donkeys and Mules

The donkey had a presence throughout antiquity and was integral to the development of what is seen as ancient cultures or sometimes ancient civilizations. The spread and proliferation of the donkey coincided with the development of urbanism in ancient Greece and ancient Italy. In many ways, humans and donkeys are entangled to create a system of movement a this is reflected in the film we’ve made. A mule is a cross between a male donkey and a female horse that produces a larger and stronger animal with greater endurance than either a donkey or a horse. Mules were a specialised animal bred for transportation and could be sold for considerable sums of money, after all Roman governors travelled to and around their provinces, drawn in a carriage, by mules.

Mules in central Italy, where they were bred in antiquity. Image by Ray Laurence, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

8) Is that a camel?

There is evidence of a drawing of a camel from a house in Herculaneum. Camels were domesticated about 1000 BCE, thus much later than the pyramids in Egypt, and we are beginning to see their spread not only across North Africa, but also into Europe in the Roman period with new finds not just from Italy, but also in the forts of the Roman frontiers in central Europe. There is clear evidence from Rome’s port town Ostia of a camel importer. These were mostly dromedaries (or one humped camels, although we are beginning to see evidence of the breeding of super camels in the Roman period by crossing Bactrian (2 humped) camels with dromedaries. It is clear until the reformation and counter-reformation in Europe that camels were a regular sight and for some reason from c. 1600 CE they disappeared. Pliny the Elder (who died during the eruption of Vesuvius) noted that camel urine was very useful for fullers cleaning cloth and clothing (Natural History 28.91).

Camel graffito from the House of the Samnite in Herculaneum. Image by Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

9) Crossing Stones or Stepping Stones

One of the features of the archaeology of Pompeii’s streets are the large stones placed across the streets that enabled pedestrians to move from the side-walk or pavement to the other side of the road. These stepping stones are found, particularly, at street intersections. They allowed for pedestrians to keep their feet dry and out of the mud or animal dung in the streets. When it rains in Pompeii, even today, the streets act as channels for water and often puddles form - as we show in the film. The crossing stones were great for pedestrians, but impeded carts as they passed through the streets on their way to destinations across the city. The study of wheel-ruts and the wear of the axles of carts on the curb stones has been studied by Eric Poehler, he explains here why it is important to know how traffic worked in Pompeii.

Crossing stones in Pompeii. Image by Ray Laurence, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

10) Paving Stones and Wheel Ruts

The streets of Pompeii were probably paved for the first time in the first century BCE. The stone used for the paving was quarried locally. If we look closely at a Pompeian paving stone, we can see that the rock is formed from a local lava that contains many crystals and is very grainy. This is quite unlike paving stones that we find in Rome or at Ostia Antica that are formed from a grey solidified liquid form of lava with very few crystals. These rocks in Rome and Ostia, when used for paving, do not develop ruts unlike in Pompeii. Thus, the ruts are a function of the type of stone chosen - the closest most local source. Once paved, the streets appeared to be like those found in the streets of Rome - however, a key issue was that the stone in Pompeii developed ruts. The Pompeians were faced with a need to replace the stone - tricky for example at the Stabian Gate, because the gate would need to be closed to traffic. Eric Poehler (who appears in our film - the dude slouching against the wall of the bakery) has found traces of iron near many ruts in Pompeii and he has suggested that the Pompeians were filling the ruts with molten iron, in an attempt to improve their streets. For more info on iron as a means of repair in Pompeii.

Wheel ruts made into lava paving Image by Ray Laurence, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

11) Referencing the work of Eric Poehler and Andrew Wallace-Hadrill

We reference two academics in the film Eric Poehler and Andrew Wallace-Hadrill. Their academic work on Pompeii has been influential in the creation of the film. Ray worked with Andrew early in his career and they taught a Uni course on the Roman city, featuring of course Pompeii. Eric Poehler has taken the study of paving in Pompeii to a more advanced level. Hence, they both appear in the video as characters contemplating the matter of traffic and the difficulties of driving a cart through the streets. Do check out their publications on Pompeii!

For more information, ask Ray’s Book a question

Get a copy of the book at Routledge.

Donate

Our supporters on patreon allow us to develop more resources for teachers, explainers, and videos!

Donate on Patreon